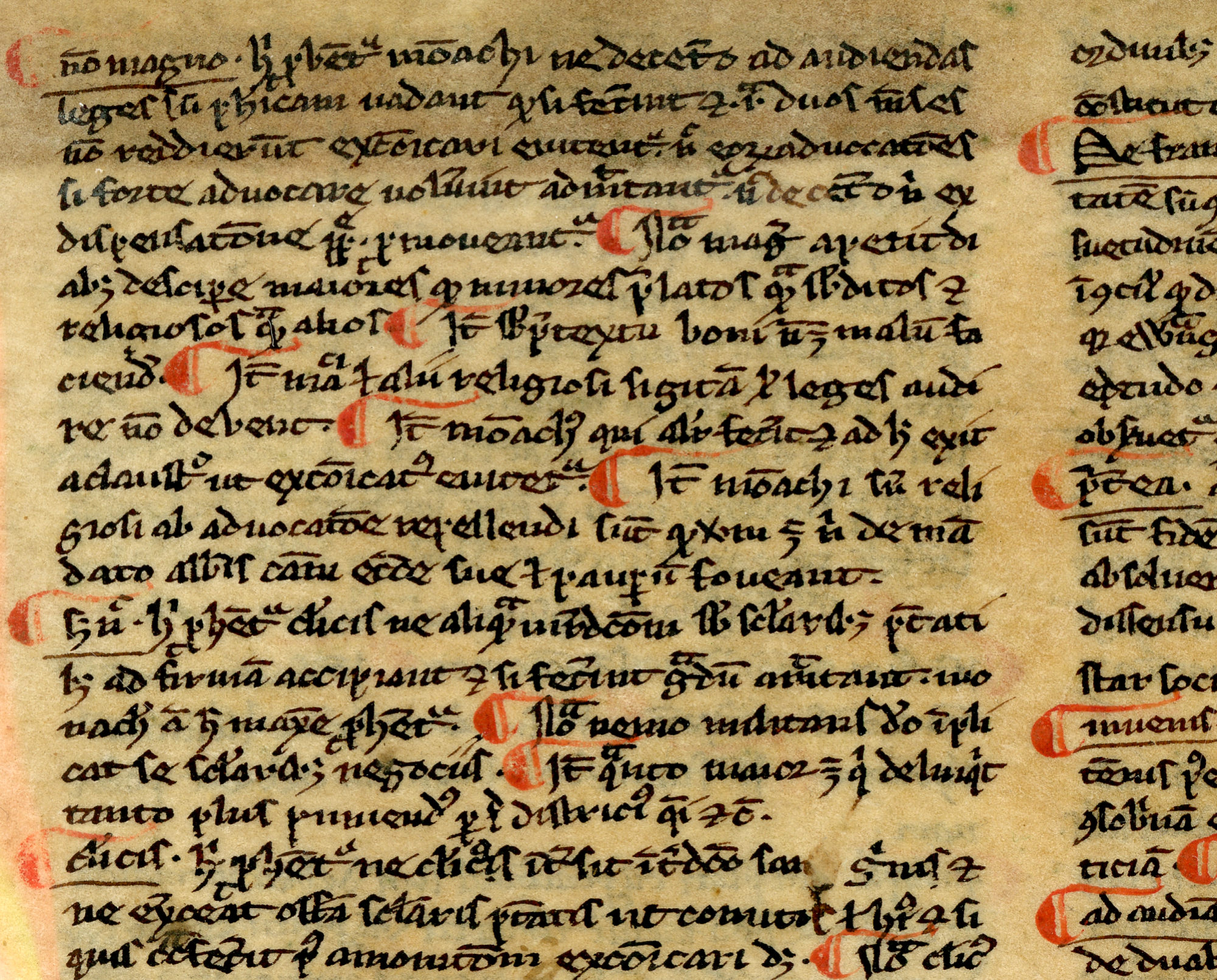

Medieval calendars are deceptively simple looking, but jam packed with potential information. They list events in Christ’s life and saints’ days (which occur on their date of death). My folio is a calendar for December, that takes up both recto and verso. Because of its size and the recto/verso thing, I believe it comes from a book of hours. I have been dedicating the majority of my efforts to transcribing and expanding the manymanymany abbreviations.

Liturgical manuscripts is a vast genre comprised of several different types of manuscripts with different functions. Books were written to serve specific purposes in Mass and in the Daily Offices and were arranged chronically according to the liturgical calendar, which had two cycles of time, the temporale and sanctorale. Calendars are most often found at the beginning of liturgical books, meant as an efficient means of identifying which events in Christ’s life and which saints’ days are celebrated on a given date. Many books in a liturgical library would contain calendars, especially missals, sacramentaries, and breviaries. The temporale, also referred to as the Proper of Time, is the basic church year, based on key events in Jesus’ life. In this cycle, the beginning of the year is 4 weeks before Christmas day on Advent Sunday. Christmas would always fall on December 25, Epiphany on January 6, Candlemas etc. Easter was the high point of the church year as it commemorates the resurrection of Christ after the crucifixion. The date of easter changed annually, because the timing depended on the Jewish lunar calendar. Easter always falls on the same date as Pesach, which is celebrated on the first full moon after the spring equinox. The sanctorale, also referred to as the Proper of Saints, provides the information for celebration of saints’ days. Often the sanctorale began with the Feast of St. Andrew (Nov 30) and end with the feast of St. Catherine of Alexandria (25 Nov), mirroring the advent- to- advent structure of the temporale. It should be noted that especially important saints are celebrated for eight days, known as an octave. My calendar contains two- On December 7, “Oct(avue) s(an)cti andree” represents the end of the octave of Saint Andrew. December 6 begins the feast of Saint Nicholas (“nvcholai epi(scopus)) and it ends eight days later when “nichalii epi(scopus) is repeated on December 14.

Trying to wrap my brain around the medieval conceptions of time and calculating dates has been a lengthy and frustrating process. Medieval calendars most often used the Roman method of counting days, which has three fixed points throughout the month- Kalends (always the first), Nones (5th-7th), and ides (13th-15th). The days in between these three points are referred to as how many days until the next fixed day. So, since Nones occurs on December 5th, December 4th would be referred to as II Nones. The left side of the calendar contains two columns for the Dominical Letters and Golden Numbers. Dominical Letters refer to the day of the week, and are represented by the letters A through G. I initially assumed A always meant Sunday, but the way it works is slightly more convoluted. The dominical letter gets assigned to a year based on the first Sunday. So in a given year, if Jan 1 is a Sunday, the dominical letter is A, and all As throughout the calendar would be Sundays, Bs would be Mondays and so on. But, if the first Sunday is Jan 2 the Dominical Letter would be B, Mondays: C Tuesdays D and so on. Knowing the Dominical Letter allows the reader to match the dates to days of the week, but you must know the Dominical letter assigned to the year.

To the left of the dominical letters are roman numerals known as Golden Numbers which show the day of the month on which the new moon will fall. These numbers are based on a 19 year cycle where the annual cycles of the sun and moon are reconciled. The Golden Numbers have the potential to be incredibly useful, however the reader has to know the current year, and what year in the nineteen year cycle the given year fell.

Can you believe I originally picked the calendar for its perceived simplicity???? I’ve played myself.