I used to believe that certain practices from the past were lost to current society as time moved on. For example, how often do you find a piece of paper today that has been made by hand? It came as a startling eye-opener then when I learned that the practice of shortening words to write quicker was not as new as I initially thought. Avid texters and tweeters should be made aware of the fact that, though the actual abbreviations change throughout history, part of the reasoning for this habit remains the same.

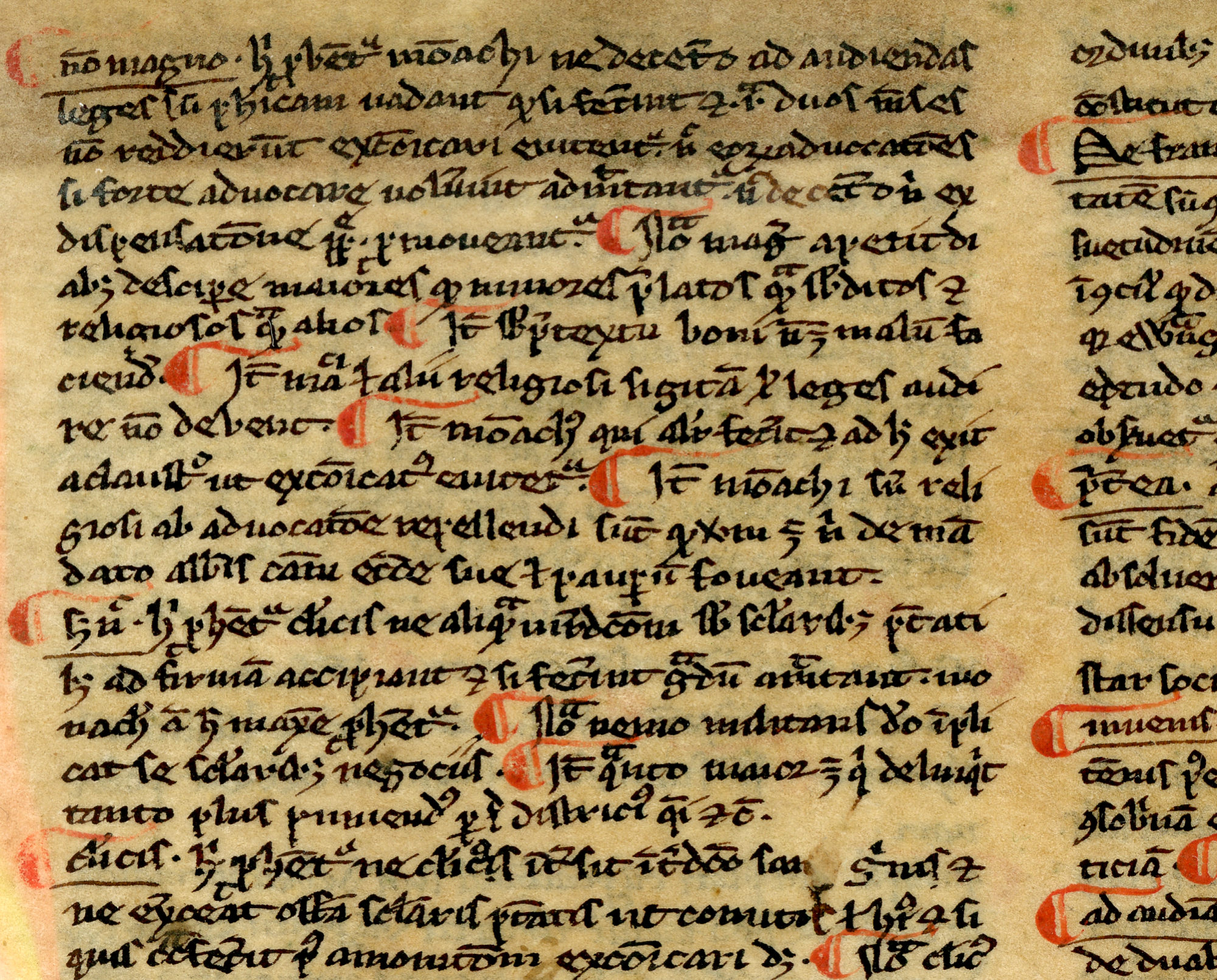

Prior to the ‘lols’ and ‘btw’ that currently dominate text messages, medieval scribes possibly used abbreviations to lessen the amount of time it took them to transcribe. Does this sound familiar to anyone? When you look at a manuscript with abbreviations there can be various dashes and amalgamations of letters (for example xpi and di) that represent condensed words. Also, as a student I often use punctuation to shorten words in my class notes (n. often stands in for the word ‘north’) because it means I can keep up with the professor. This is not an original idea or practice because Adriano Capelli notes this exact form of abbreviation in his dictionary on medieval abbreviations. With the realization that abbreviations are part of our history, ’lols’ and ‘omgs’ then signify the present generation’s role in the story of human communication.

For anyone investigating medieval abbreviations, they know that it can be a frustrating process. The urge to scream ‘what does this mean’ or ‘why would you write that’ indicates that what was once common knowledge to these scribes has disappeared over time. It is interesting to make a comparison between a modern historian studying medieval abbreviations and one who, centuries from now, investigates twenty-first century abbreviations. No doubt this scholar will experience a similar frustration considering how rapidly our abbreviations change. Furthermore, the understanding that ‘lol’ does not necessarily mean someone literally ‘laughed out loud’ is important contextual information future academics might not possess. This comparison demonstrates the importance of the context that lies in every abbreviation. I know that ‘g2g’ stands for ‘got to go’ because I grew up with this knowledge, just as a scribe might have known that ‘xpi’ represents ‘Christi’ because he transcribed it multiple times. Additionally, future historians will have a difficult time decoding our abbreviations due to the emotional meaning often lurking in our text messages. While sometimes I lament the task of decoding a medieval manuscript I certainly do not envy historians who examine twenty-first century abbreviation.

Abbreviations did not magically appear alongside the growth in texting. This is a practice with strong historical roots, evident in the presence of abbreviations in medieval manuscripts. Even students today who try to transcribe their professor’s lecture employ a technique these monks used, suggesting that the technique lingers as well. Next time I hear someone complain that texting words like ‘ppl’ (people) and ‘pls’ (please) signals the downfall of written language I hope this person is ready for an impromptu history lesson.