Hello everyone in Medieval Manuscripts,

This is the blog post for the seminar that I did a week ago regarding Book History. I proposed four different questions relating to the cataloguing of book history and the readings that we had on it. Three of which got answered. The first of my questions to be answered regarded why we were given the readings in the first place. The second question that was addressed dealt with the ideal copy of a manuscript. This question dominated most of the class discussion, as it branched into how an ideal copy could be interpreted and what we as scholars hoped to gain from it. The final question to be discussed surrounded the use of electronic media in this field of study, and the benefits and drawbacks that came from its use. This question seemed to be relatively easy to answer for the class, as the group appeared to reach a consensus. In this blog I will do my best to recap the discussion that happened in class, so I hope that it’ll be useful.

The best place to start the recap of the discussion is to begin with the beginning of the class. Professor Saurette described that there were several different intentions and minds that went behind writing a manuscript. For Medievalists, it is important to consider who could write during this time period, as their biases were going to be apart of the text. On top of this, many manuscripts are written in different languages that half to be translated for their words to be read most of the time. Changing the meaning of many of these manuscripts. Interestingly, the class came to the general opinion during this lecture that there was no real way to know the authors intentions, making most assumptions about them just educated guesses. This process of writing unintentionally answered one of my posed questions regarding why the readings were assigned in the first place. The idea seemed to be to show the complexity of Medieval writing, and how different values and intentions mixed into a single work. This idea of intentions behind writing and the problems of translation provided good background for the discussion regarding the ‘ideal copy’.

The second question discussed focused on what an ‘ideal copy’ would include, and would this ideal version just be in pristine condition, or would it have different content depending on who was imagining it? The class agreed that the content would be different depending on who was looking for it, suggesting that having an ideal copy was an impossibility. The class also noted that importantly, first copies and rough drafts are often not the best versions of text. Eventually leading to the question of why such a thing was so highly coveted to begin with. The class discussed the ideal version as being a sort of mythical piece of evidence. As finding one document that was irrefutable and in ideal condition was viewed as the pinnacle of scholarship. Drawing on what had been discussed earlier about the lack of clarity concerning an ideal copy, the class suggested that a better goal or pinnacle should be a critical edition. A document that guides a reader through a given text by making use of other sources. Thus, providing more information for a reader if they chose to learn more. The idea of a perfectly preserved manuscript and what could be gained from just being able to hold it related to another question that I posed last week.

The question was all about how important a physical copy is during the age of digital text and its availability. The class was unanimous on the stance that there is a lot of information to be gained from the physical copy of a manuscript. There is a certain uniqueness about a document that is still intact in its original form. So, to have the manuscript limited to a simple file prevents that sense of uniqueness from being experienced. The benefits of electronic media were also shared amongst the discussion group though. Including the ability of a text to not be exposed to harmful conditions, preventing any further degradation. It is also helpful to be able to zoom in on a given text, as well as invert it and change its properties in order to identify some features that would not normally be visible. The class thus concluded that there is a certain use for technology but that physical copies should not be disregarded.

Overall, the class discussion went very well. The class was engaged with the material, drawing on discussions that were had last week concerning personal bias whilst simultaneously understanding that when reading a manuscript, it isn’t just the individual authors voice coming through. This allowed the class to discuss the ideal copy and all the implications that came with it. Both in terms of content and its condition. Furthermore, suggesting that such a thing isn’t possible, but that there is a more instructive way to help readers through a text. The idea of an ideal pristine version of a text also allowed the class to answer the question of how useful physical copies still are in modern scholarship. With a decision being reached that they do still have a purpose, but that electronic media does have a place as well. In conclusion, I am really pleased that my questions were able to cultivate such a lively discussion, and I thank the whole class for their participation.

A new year

It is now the end of November and it feels like the term is quickly coming to an end. I am looking forward to reading all the work that my new students will be producing in the coming weeks talking about their experience working with medieval fragments and working in Carleton’s Book Arts lab!

Building a Website for Medieval Artefacts — What did I Learn?

This year we decided as a class to undergo the exciting task of putting on our very own manuscript exhibition in the display cases of the History Department. During out discussions, I was struck by the fact that our hard work would only be on display for a short time. If we could make this exhibition permanent, we could show off our work for years to come. But the university space is limited and could not accommodate such an exhibition. However, building a website to house this exhibition promised longevity. Therefore, myself and the other members of the website team came together and began work on Medieval Ottawa, a companion to the exhibition.

Our first task was to chose a platform. After experimenting with Omeka, WordPress, and Wix.com we decided that WordPress, with the various plugins it offers through our student hosting package, would give us the desired layout and usability. Our main concern was whether the platform we chose could host the high quality images necessary for our audience, who would need to see the fine details of the objects. Omeka had this ability, but ultimately lacked the functionality we wanted for future students and researchers. Wix.com lacked open-source options, and was therefore less student-friendly. WordPress was the Goldilocks of the bunch, perfect for students with its open-source usability and it is capable of hosting high resolution images.

Once this was decided our team member Callum began researching how to incorporate IIIF framework or Mirador viewer into WordPress. As we have written in a previous blog post, this proved difficult to accomplish without direct access to the university’s server and this task was ultimately abandoned. Nevertheless we were still able to host our high resolution images and implement a zoom function despite the drawback.

Matt was tasked with filming interviews for the website and these were uploaded to the Medieval Book Youtube account to be embedded into the WordPress website. You can watch the videos here. We also made use of the University’s Media Commons recording rooms to record Shamus McCoy reading the Latin transcriptions of the objects in our exhibition. We felt this would be beneficial for the seeing impaired and would offer an auditory way to engage with these medieval works, which we so often understand as solely visual objects. You can hear these recording under the “transcription” tab for nearly all of the folia in our exhibition.

We wanted to ensure that the research on our manuscripts were preserved long after the exhibition was taken down, so we set up a Metadata tab on each of the folia pages on the website. This is an organised collection of the information each student in the course gathered for their respective folia in the Fall term. This process was the longest: the information was first gathered, reviewed, reviewed again, organised, standardised, and finally reviewed again before it was imputed into the website. This was to ensure that researchers and students could easily access the data for these objects. Having correct (to the best of our knowledge) information on display was extremely important to our team, and we encourage researchers to comment and correct the data if possible.

The time and effort that went into creating this website was immense. The website team at times found ourselves working for 8+ hours in the History Department’s Digital Humanities room. I cannot thank my team enough for their hard work and patience in seeing our vision to the end. Throughout this process I learned many valuable lessons, I will name a few here. I learned how to lead a team by setting attainable tasks, providing assistance and encouragement, and ultimately doing whatever I could to ensure we all reached our end goal. I also learned the art of delegation. So often in my undergrad I found myself carrying the load of a group project because I was afraid to let go of tasks I deemed to important to not handle myself. This year I learnt to trust in the strengths of my teammates by allowing them to take on the tasks that I would normally attempt to do myself. This was an invaluable lesson that I will surely carry with me. When we set out to build a website, I did not realised that on top of gaining experience in website building and digital humanities I would also learn some of the most important skills for a student to take away from university: how to not only work but thrive within a team.

Manuscripts on Display: Student Engagement with the Physical Book

When our class discussed creating an exhibition for Carleton’s “lost” manuscript fragments, we were confronted by the question of audience. Who would be interested in visiting our display? What knowledge do they bring with them and what knowledge do we want them to take away?

As university students who are enthusiastic about the medieval past, our aim was to delight but we hoped to entice visitors to learn more. Thus, the exhibition team set about choosing the most beautifully decorated, shimmering and detailed fragments, those with illuminations that would excite— from exceptionally brilliant flora and fauna to the most haunting portraits of executions and angels.

Early in this process, I had the opportunity to put our fragments and manuscript books on display for the students of a second year course on Medieval Europe. This was to be a one-time exhibit and students were tasked with providing post-workshop feedback. This was a unique opportunity to understand what students take away from engaging with physical codices and fragments.

Of course, as the coordinator I had preconceptions about student’s expectations and knowledge of the Middle Ages. In fact, we had spent multiple sessions together discussing medievalisms: popular beliefs about the middle ages, with the likes of Robin Hood, King Arthur, and the notorious Black Death appearing as distinctive features of the period. Moreover, most of the student’s assignments required the examination and analysis of source documents. These were often transcriptions and translations (often translations of translations) into modern English. With many steps removing the student from the physical document, it is beneficial for them to engage with these documents as physical items— What better way to understand the physicality of these documents then through not only seeing them through glass but engaging with them!

In consultation with Marc Saurette (Department of History; Medieval and Early Modern Studies) and Llyod Keane (Archives and Rare Book Coordinator) I began pulling sources from the shelves, keeping in mind to demonstrate both the beauty and the dynamic culture of the medieval past. Beginning with medievalisms, we pulled from the shelves of Carleton’s Archives and Research Collections (ARC) an early modern version of Caxton’s edition of Mallory’s Le Morte d’Arthur which features the original Middle English spelling. I included Gerard’s Herball (a herbology handbook originally published 1597) so that students could amuse themselves reading this vernacular text. This was a particular hit among the class, not only because they could read and sound out the early English, but because this allowed them to find both extinct and fantastical plants. One astute student mentioned they were intrigued to find post-columbian exchange items (such as potatoes) in the book.

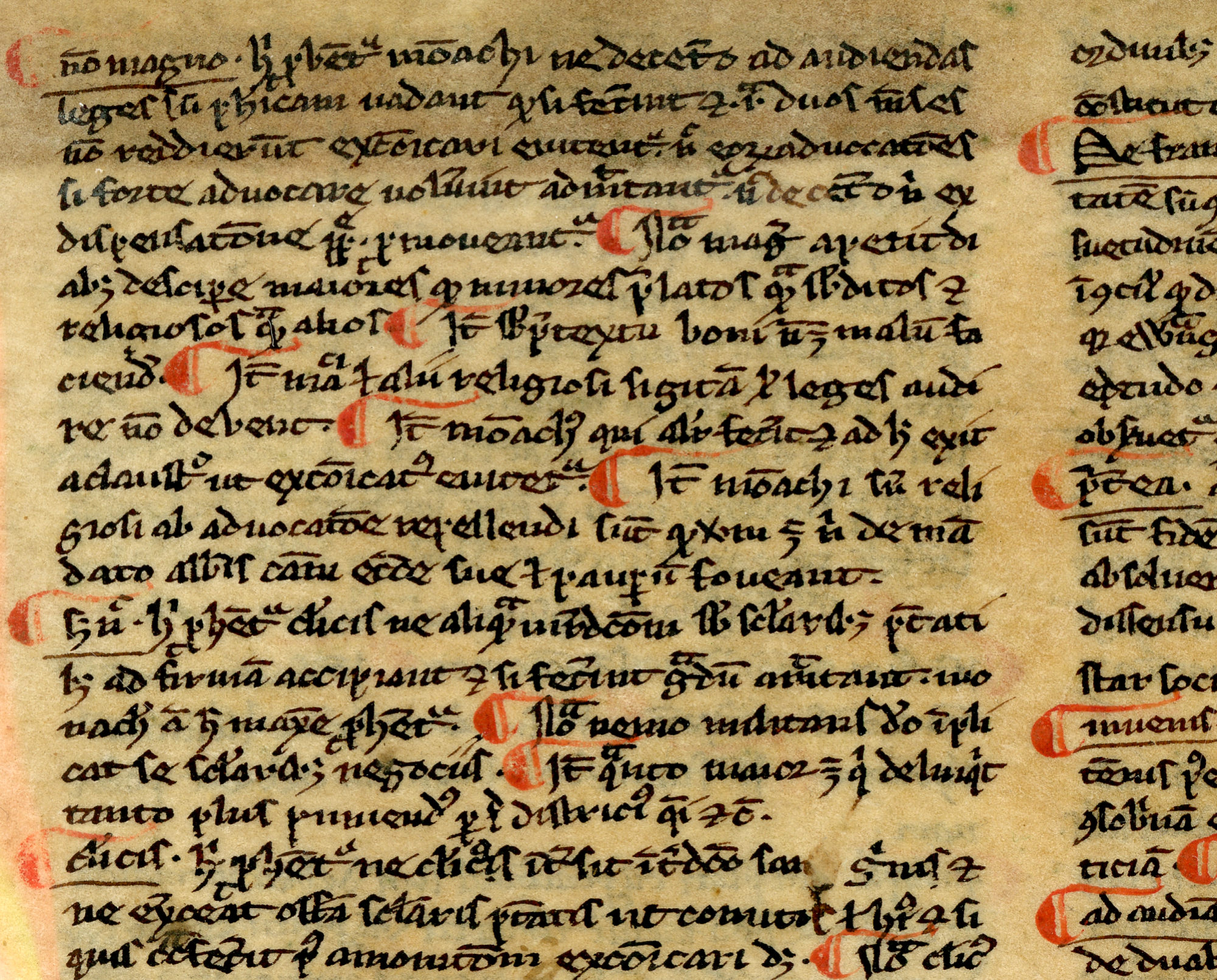

Throughout the course we discussed the rise of notaries and universities during the Middle Ages. To provide a sense of what these documents may have looked like, I included both charters held in ARC (letters on the topic of the King’s rents) and a student copy of the Commentary on Pope Gregory IX’s Decretals. One charter is a chirograph, a document written in duplicate on a single parchment with the words “chirographum” in the center and then cut through to later establish the authenticity, the other a common deed accompanied by a broken red wax seal. A student who plans to study law spent a good portion of time with the chirograph; another student found the notes on Decretals compellingly relatable to our modern methods of learning through notetaking.

However, it seemed the majority of students were less concerned with the content of the documents themselves and far more interested by their physical aspects. The amount of time and labour taken to create a manuscript book, the use of animal skins for parchment, and even the process by which monks would learn to become scribes fascinated them above all. To be able to touch the rough and wrinkled vellum, see the gold leaf illuminations in person, and to smell the scent of an old tome whirling up as you turn the massive pages were recurring mentions among the student’s responses. They connected these physical objects to the historical work they had been doing throughout the year, writing that this experience was invaluable to them for the opportunity to have a glimpse into the past. For some, it provided an understanding of the immense reverence that medieval people could give to manuscripts books.

I would say that from what I found, students were indeed drawn to medievalisms but were very interested in the physicality of the medieval book. Not only were they drawn to the beautifully illuminated works, they found charm in the rough and crinkly parchment of these well-worn codices. I hope this brief exhibition as well as the exhibition in Carleton’s History Department, Carleton’s Lost Manuscripts, inspires future codicological pursuits!

Thanks for reading!

Kate

Avoiding the Tower of Babel: Week 19 Discussion Reflection

The author of Genesis chapter 11 lays out the story of the tower of Babel: Mankind, in their pride, built a great tower reaching the heavens. God was not pleased with their actions and so He “confused their language so they would not understand each other”. As a result the tower never got completed since there was no common language anymore. An interesting story about pride and an explanation for the development of language. But imagine if there was a universal language, a standardized form with the potential for adaptability, think about what we could accomplish.

The potential universality of Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) and its contribution to preventing a scholarship that cannot be collaborative due to the hindrance of language or formatting is an impressive ideal to seek after. The TEI enables greater accessibility and greater movability through the use of tools such as schemas(TEI lingo) or the development of new a schema especially when the source material is unique, since not every source can be standardized. TEI allows and encourages building off existing tool sets and relying on other scholarship rather than reinventing the wheel and doing redundant work. Furthermore, it attempts not to compromise what the text is and or what it will become in the future.

During our in class discussion around TEI in week 14, I asked the question “to what extent can TEI accurately represent a source in a digitized form- what is lost through digitization”? Now, this might be an old and antiquated question but is important to consider and Professor Saurette offered an answer. To summarize his words, the TEI’s purpose is not to create an all immersive experience to replicate, or replace, the physicality and materiality of a source but rather the TEI is focused on creating an online version of the key components of the source. Digitization is not used as a replacement but rather a supplement to the real deal, and even with all the immersive technology, all the sound scaping and the appeal to the senses, there is no way to do away with tangibility. When I was younger I went into Action Packed Comics in Kingston looking for MTG card singles and I heard a gentleman ask the owner if he thought online comic books would put him out of business. A legitimate question and one that intrigued me. The answer replied with confidence: “It’ll never happen. People love the feeling, the smell and physically owning a comic book and nothing can replace that- the nostalgia is what people pay for more than the stories”. A sentiment that can be applied to DH but I digress and realize this blog post is a buck shot as opposed to a slug.

The point I am making is that the TEI is a great initiative and opens up the possibility of greater accessibility and collaboration between scholars. Professor Shawn Hawkins stated that if he attempted to Encode all of the Roman poet Catullus’ poems and the accompanying commentary, that awkwardly occupies the margins caging the poems, it would take him a lifetime of work but through collaboration he can focus on the finer points of interest. It’s incredible to think about the completion of our final project and how collaborative the journey has been- anyone of us would be hard-pressed to do the work we’ve done all on our own. But as a community of scholars, a class, we began building on the foundation of skills, laid by Professor Saurette, that we developed in first semester and now, in second semester, we’ve built a tower, a mighty Digital Tower… let’s hope we didn’t offend any jealous gods along the way.