Oral interviews and pursuing an individual’s story through the mode of videography has become a passion of mine during my undergraduate degree. In my third year I had opportunity to work with Professor John Walsh in a historical practicum course during which myself, and another student, performed oral interviews with long-time members of the Alpine Club of Canada. Being able to engage with people on a personal level, with all the emotional navigation that accompanies it, allowed me to encounter a history that was not merely held in books or journals but in people’s lived experiences, in their visages. Seeing a person’s face change and hearing their vocal inflections when they are leading their mind through the memory palace of their experiences is truly something to behold and makes history much more alive than, dare I say it, a book. For the final project in HIST 4006 A I had the opportunity to yet again sit down with individuals, this time peers of mine, and flush out their experiences handling Medieval manuscripts.

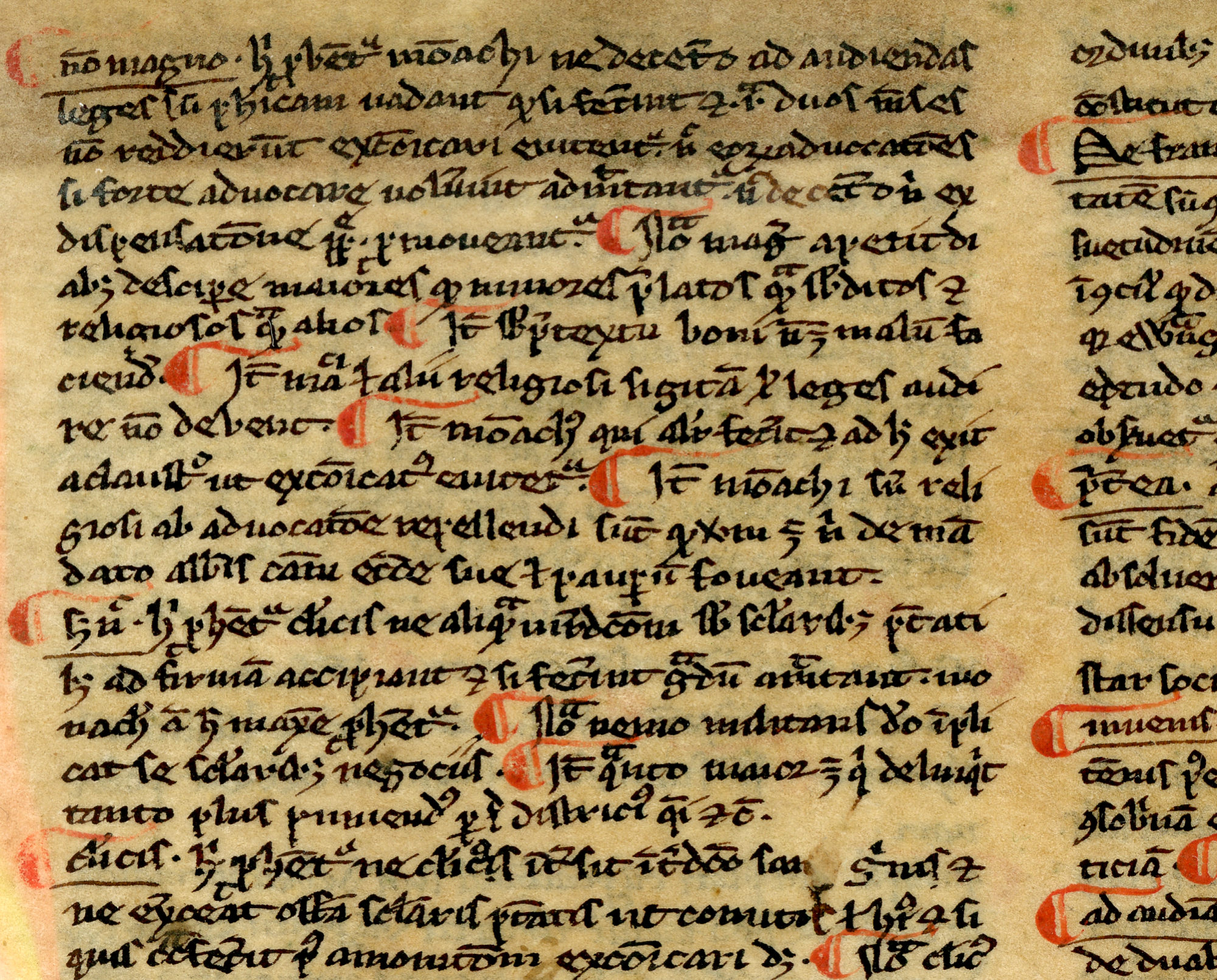

Lyn Abrams notes that oral history is more than just asking a question and getting an answer but that the interview is, “a give and take, collaborative and often cooperative, involving information-sharing and autobiographical reminiscence, facts and feeling.” (1) Abrams principle of fluid dialogue and a built relationship between the interviewee and interviewer was something that I applied to each interview I conducted for this project. Before the interview would begin I reminded the interviewee that it would be very informal and not to worry about answering all the questions I had; I wanted the interviews to be as organic as possible and not push an agenda filled with assumptions. As I interviewed my peers a golden thread slowly began to emerge from the great tapestry of interwoven encounters: the experience of physically handling the manuscripts. Each one expressed their surprise of being allowed to handle a 500 year old, in some cases older, manuscript. They talked about being able to feel the parchment, the gesso from the illuminations, and utilizing new skills to determine provenance and genre. The more the interviews carried the more my peers noted the uniqueness of their experiences within Digitizing Medieval Manuscripts.

Part of the reason I thought it would be a wonderful idea that the project website host videos was to not only showcase the work done by students, but also to allow the students to curate their own experiences and by doing so put a face to these manuscripts, a face filled with experiences of its own. These interviews were also a great time of self-reflection to wrestle with the reality that we were not only enabling greater accessibility to these manuscripts through curating an exhibition, online and analogue, but also that we had become “producers of knowledge” (To borrow Professor Saurette’s words). It is my hope, and that of my peers, that our scholarship throughout this project will enable other Carleton students to grasp the potential available to them while studying in University and hopefully spur them onto to become contributors and collaborators of these manuscripts in future projects. That they will weave their experiences into the tapestry of academia and stand back and marvel at their accomplishments, just as we have ours, and say “There is more to be done”.

- Abrams, Lyn. Oral History Theory. 2nd ed, New York: Routledge, 2016, p. 21.